Vocal

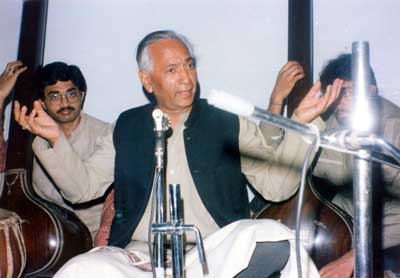

| The son of the legendary Pt. Krishnarao Shankar Pandit and is currently the seniormost representative of the Gwalior gharana of khayal. Now over 70, he continues to perform and teach students like his own daughter Meeta Pandit. |

Irfan Zuberi: Pandit ji, please tell us something about Gwalior and its cultural heritage.

Pandit Laxman Krishnarao Pandit: Gwalior has been described as the ‘cultural capital’ of India by Fakhirullah, one of the governors of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb.

I will talk about the golden period of Gwalior which was during the reign of Raja Man Singh Tomar (1486-1516). He is known as the ‘father of dhrupad’ due to the patronage he gave to music in general and this form of Indian classical music in particular. He was the one who got the ancient dhrupad verses which were earlier in Sanskrit and Pali translated into Braj bhasha. One strand of scholars contend that Braj bhasha came into existence in Gwalior and then spread all over India.

Raja Man Singh Tomar was a great visionary and collected all great musicians of the country at the time in his court and it boasted of 7 nayaks (experts of both theory and practice of music). I remember the names of Nayak Baiju, Nayak Bakhshu, Nayak Dhondu and Nayak Charju. It is also a historical fact that out of a total of 36 musicians in the country during those times, 20 were in Gwalior. Raja Man Singh Tomar organized a music conference in those days and then he wrote the book ‘Mankautuhal’ which got lost in the course of history. However, I believe it was translated into Persian by Fakhirullah a copy of which still exists somewhere.

In the palace of Rani Mrignayani was a music school where students used to come from in and around Gwalior and learn from the legendary Nayaks of the court. Tansen also received his training in this school. In this way, it can be said that Raja Man Singh Tomar laid the foundation of music in Gwalior and thus began the Gwalior parampara. I refrain from using the term gharana since it is a small word whereas my intention is to indicate a larger tradition. The most sparkling star in this grand parampara has of course been the legendary Miyan Tansen.

Then came the dark period of Gwalior when the palace was turned into a prison and all the magnificent artifacts were mauled by the armies of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. This palace was very special because it had 7 stories underground where the musicians used to sit and practice. Even in those days when there was no electricity, the 7th underground storey was designed in such a way that it had light and water.

Scindias were the next dynasty to take Gwalior under its patronage. They were the representatives of the Peshwa dynasty and were very fond of the arts. I will talk about Daultarao Scindia in particular. He had a number of great musicians in his court who used to great salaries in hundreds in those days when even the top officials of the court used to get a salary of Rs. 20! What made it even better for these musicians was not just the ambience and patronage of the Gwalior court but also the love and respect they commanded in the hearts of the common people. So much so that in times of dire need, musicians used to go to the money-lenders and pawn their raags in return for money!

IZ: It seems understandable why music flourished in such an environment. Pt. ji, tell us about the foundation of the Gwalior gharana of khayal gayaki and about its originators and how your family came to be linked with this tradition.

Pt. LKP: There was a court musician during the time of Daultarao Scindia called Ustad Nathan Pir Bakhsh and his maternal grandsons were the legendary Haddu, Hassu and Nathu Khan. The main musician in the court at the time was Ustad Bade Mohammad Khan who was famous for his taanbaazi. The trouble however was that there was a relationship of professional jealousy between Ustad Nathan Pir Bakhsh and Ustad Bade Mohammad Khan due to which the latter refused to teach the former’s maternal grandsons even though they belonged to the same tradition of Shah Sadarang. The king solved this problem by asking Haddu and Hassu Khan to sit under his throne hidden from the eyes of Ustad Bade Mohammad Khan while he sang in the court! The two youngsters were already talented and knowledgeable and with this impetus to their style, they picked up quickly and became good singers of khayal gayaki in their own right. This can be said to be the critical moment in the development of khayal gayaki and all the other gharanas of khayal thus owe their existence to Gwalior.

One day the king asked Ustad Bade Mohammad Khan to sing and asked Haddu and Hassu Khan to follow. Bade Mohammad Khan saheb was amazed at the singing prowess of the two youngsters and felt betrayed. He left the court but did something nasty before leaving. There is a particular taan called the ‘kadak bijli ki taan’ which can only be employed once during a performance due to the pressure it puts on the lungs. Bade Mohammad Khan praised Hassu Khan and asked him to take the same taan a second time. When Hassu Khan took the taan, his lungs got ruptured. Ustad Nathan Pir Bakhsh tied his turban around Hassu Khan’s chest and asked him to complete the taan even if it meant his death! Hassu Khan died prematurely but Haddu Khan lived on and taught many people and remained an unparalleled khayal singer all his life.

It was during this time that my great great-grandfather Pt. Ramachandrarao Chinchwadkar came to Gwalior. Him and his son Pt. Vishnu Pandit Chinchwadkar were great scholars of Sanskrit language. [Over time, Chinchwadkar got dropped and we just became Pandits.] They used to do Sanskrit katha and tell legendary stories accompanied with music. They came in contact with Nathan Pir Bakhsh who was looking for someone with good knowledge of Sanskrit for Hassu and Haddu Khan. Haddu Khan saheb was very impressed with the four sons of Pt. Vishnu Pandit Chinchwadkar and accepted them as students. Haddu Khan saheb led a very strict life and practiced for 9 hours everyday till his death saying that people could say that I am old but I cannot tolerate people saying that my gayaki has become old! So my grandfathers had the good fortune of learning from someone like him and later Nathu Khan saheb who was also a great master of tarana and trivat. After Nathu Khan saheb’s death, my grandfather Pt. Shankarrao Pandit and my father Pt. Krishnarao Shankar Pandit learnt from Ustad Nissar Hussain Khan saheb, who was the adopted son of Nathu Khan saheb.

After the death of Jeevajirao Scindia, the council of ministers of the court took over and decided to slash the salaries of musicians at which point Ustad Nissar Hussain Khan saheb starting living at our place where he stayed till his death. He was called a ‘kothiwala gavaiyya’ which meant that he had a kothi full of knowledge in terms of raags as well as compositions for dhrupad, khayal, thumri, tappa, tarana etc. This is the way music came in our family and it has stayed ever since. My father also started one of the oldest music schools in India called Shankar Gandharva Vidyalaya in the year 1914. We are now the progeny of Haddu and Haddu Khan saheb since their family does not exist anymore.

IZ: Panditji, I want to ask you about the intermingling of various gharana styles to such an extent that it is practically impossible now to pin down the gayaki of a particular gharana today. Within the Gwalior gharana, there has been such a wide variety of people ranging from Pt. Vinayakrao Patwardhan to Pt. D. V. Paluskar to Pt. Omkarnath Thakur to Pt. Rajabhaiyya Poochhwale and others. I want to ask you about the salient and defining characteristics of the Gwalior gharana.

Pt. LKP: First of all, gayaki depends upon the amount of taleem you receive. Secondly, when there is a large family, it becomes difficult to recognize the various styles of individuals. After all, music is a reflection of society and when it becomes difficult to pin down individuals in society in terms of their identity as well as personality traits, how do you expect the scene in Indian classical music to be different? However, discerning people can notice differences between various practitioners. The fact is that the fundamental and basic principles of all the singers you have mentioned are the same even though their individualistic style may differ. The emphasis on ashtang gayaki and discouragement to copy one’s guru is critical. The eight elements of ashtang gayaki are: alaap, bol-alaap, taan, bol-taan, layakari, gamak, meend-soot and khatka-murki-zamzama. These principles are used in the development of every khayal we sing. The importance of each raag in accordance to the bandish is also very important. Gwalior parampara people sing in a wide variety of taals ranging from Tilwada, Ada-chautaal, Teentaal, Ektaal and others and practice forms such as khayalnuma tarana, tappa, ati-drut tarana, tap-tarana, tap-khayal, bandishi thumri, ashtapadi and others which rarely form the repertoire of singers from other traditions. So you can understand that someone with so much masala will never run out of variety!

IZ: Tappa is a form which seems unique to the Gwalior gharana. However, not much is known about its structure and characteristics. Please elaborate.

Pt. LKP: Tappa is the most difficult part of khayal gayaki. The name comes from the Punjabi word ‘tapna’ which means to jump and hop. The etymology tells us everything about its nature and characteristic since while singing a tappa, the voice is always on the move doing rapid jumps and hops. Ghulam Nabi’s son Miyan Shouri gave a classical twist to this style because his voice was very flexible. He traveled to Punjab and the North West Frontier Province taking elements from the folk songs of the region and incorporated them within his style to make tappa. Gwalior adopted tappa and its essence got inextricably linked with tarana, thumri, khayal, pada etc. It is very difficult to sing it because it requires khanakdaar and daanedaar taans to present a polished tappa. It also demands a command over the laya which is not easy to attain. The other reason why it has gone out of vogue is because there are not too many people who want to listen to it anymore. I can tell you from my experience that all concerts I gave in Punjab during a particular circuit, I was requested to sing a tappa in each concert and I thoroughly enjoyed since people demanded it!

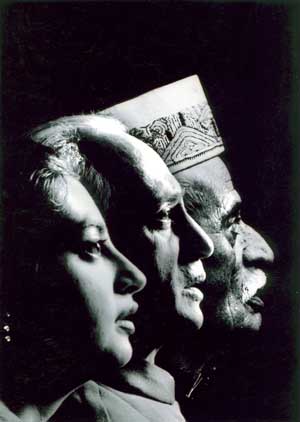

Krishnarao Shankar Pandit, Laxman Krishnarao Pandit and Meeta Pandit

IZ: Panditji, tell us a little about your initiation into music and your training under your illustrious father.

Pt. LKP: Our family has always had a treasure-trove of music. Ever since I remember of being conscious of myself, I have been listening to music and learning music within my family. Within Gwalior parampara, the method of teaching is very scientific and there is a step-by-step and phase-by-phase development of the student by the guru. I practiced the various alankaars and paltas in the beginning and my father placed great emphasis on development of a proper voice culture. Then I proceeded to do swar abhyas and the sargams of various raags and then finally I moved onto compositions and the presentation of the overall gayaki. My father was a strict taskmaster and made sure I did regular riyaaz. He was the emperor of layakari and was an unprecedented khayal singer and I consider myself blessed to be his son and his shishya both!

IZ: You have spent your entire life immersed in music. How has it been and what would be the one fundamental thing you have learnt in your life?

Pt. LKP: I have heard great masters, both live as well as recorded since I was working with All India Radio and made sure that I heard each and every recording available in the archives properly. I went through a great tragedy in my lifetime. I lost my son Tushar to a road accident. He was coming up as an excellent musician and this was a great shock to me. If there was anything which kept me stable during such a time, it was music itself. I think of music as a responsibility on my shoulders and think of myself as a soldier of the Gwalior parampara. My daughter Meeta took the responsibility upon her shoulders and has the distinction of being the first female musician in the family. However, there is still a long way to go and I want to do a lot more things in music to give back to it in whatever token as a reciprocation for all that I have gained from music.

IZ: In today’s atmosphere of light music, popular music and fusion music, how do you see the future of Indian classical music?

Pt. LKP: There is no doubt about the fact that Indian classical music is becoming poorer by the day. All the spread which it has achieved has been in terms of quantity alone and often at the expense of quality. Learned discerning listeners are also very few in number nowadays. It depends on the practitioners and sadhaks of Indian classical music to ensure that this situation improves. This can only happen if they remain committed to the cause of their traditions and place emphasis on good taleem. I hope it happens but unfortunately I do not have a peephole into the future!