Sarangi

|

Ustad Sabri Khan is a representative of the Moradabad gharana of sarangi playing. He has the distinction of being an accomplished accompanying artist as well as a brilliant solo performer. Even at the age of 78, he continues to give solo recitals and teach students instrumental as well as vocal music.

|

Irfan Zuberi: Please tell us something about the sarangi.

Ustad Sabri Khan: The epithet of “saurangi” is perfect for the sarangi. It has a hundred colours and probably many more. It is capable of playing any style of music – from dhrupad, khayal, tarana, thumri, dadra, tappa, kajri, chaiti to folk song, ghazal, geet, bhajan etc.

It is an ancient instrument dating back to the 13th century. It finds mention in all the major historical and musical texts such as the Sangeet Ratnakar, Sangeet Parijat, Ain-i-Akbari etc. According to Indian musicological tradition, the sarangi comes under the generic name veena indicating the entire complex of stringed instruments. There exist many kinds of sarangi – for example, sindhi sarangi and jogiya sarangi which are different in structure and in terms of the number of strings they have.

There is an interesting story about the development of the sarangi. It is said that once Hakim Jali Noos was passing through a jungle and he saw the decaying corpse of a monkey with all its intestines dried out. He plucked them and a sound was emanated and he thought of using these intestines as strings. So, even today, the strings of the sarangi are made out of the intestines of goat.

The present-day sarangi is constituted in reflection of the human body with a head, face, chest and stomach. This also suits its status of being hailed as the one instrument which is closest to the human voice!

It has a total of anywhere around 35-40 strings with 3 main playing strings and the others being sympathetic strings. It can be said that the sarangi is a complete instrument.

IZ: Please enlighten us as far as the solo and accompaniment status of the sarangi is concerned.

Ust. SK: The sarangi has always had a dual status of being both a solo instrument as well as an accompanying one. It used to be played solo in the earlier times as well contrary to what some people might say. It is only because of its proximity to the human voice that it started being primarily used as an accompanying instrument with all styles of singing.

Sabri Khan and Krishnarao Shankar Pandit

Let me tell you something about the art of accompaniment. It is much more difficult than solo sarangi playing. It is an art which comes slowly and with experience. If you choose to be only a soloist, mastery over even 20 raags will be enough for your entire career but if you are an accompanist, even 1000 raags will fall short of expectations. The interpretations of raags, the employment of different taals etc. become decisive factors over which the accompanist has no control. Thus, good accompaniment is a difficult skill to master and only a very few people can play with a wide diversity of styles of singing.

IZ: The sarangi is a fast dying instrument. What is the reason for its decline?

Ust. SK: The sarangi is a difficult instrument. That is one reason why not many youngsters are taking it up. The other major reason is related to remuneration given to accompanying artists. It is really sad that the accompanying artists are paid 1/3rd or even 1/4th of what the main artist gets whereas he puts in the same amount of hard work and has to concentrate hard to follow the particular style of the main artist. This is the reason why many famous sarangiyas trained their sons to be either vocalists or advised them to play other mainstream instruments such as the sitar or the sarod.

Another reason is the fact that good teachers of sarangi are dwindling. Some of the best sarangiyas died unnoticed and no one realized the treasure-house of musical knowledge they possessed. Others chose not to spread their knowledge too far and wide and kept it with themselves. I am against this attitude. I feel that music is to be shared and given to as many people as possible so that it lives on and continues to spread regardless of any boundaries. It is because of the few people who did give generously that it has come to us and it is our duty to give to others so that it continues to grow from one generation to the next and so on.

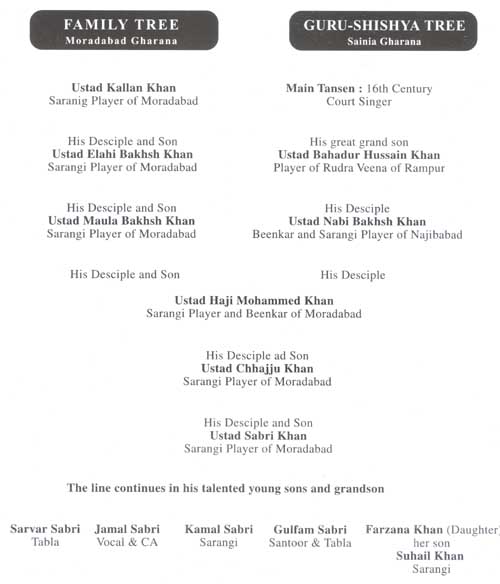

IZ: Tell us about the Moradabad Gharana of which you are an exponent.

Ust. SK: You should keep in mind that after three generations, a family of musicians is fit to be called a Gharana. For example, if your grandfather and father have been musicians and you are also one, you can stake a claim to be a Gharana.

|

Moradabad has been the place of great musicians for many generations. The four brothers and Ustads Chhajju Khan, Nazeer Khan, Shuja Ali Khan and Mubarak Ali Khan were born there. They later shifted to Mumbai and their disciples named their Gharana the Bhendi Bazaar Gharana after the place the 4 brothers used to live. In tabla, Moradabad has been especially blessed. Legendary tabla players such as Ustad Masit Khan and his son Ustad Keramatullah Khan and the great Ustad Ahmedjan Thirakwa were born in Moradabad. Had these greats taken the name of Moradabad, the city would have a place in the cultural map of the country. But, sadly, they did not do so. Sabri Khan |

I wanted to make sure that Moradabad comes to the forefront as far as the world of Indian classical music is concerned and so I always took its name.

IZ: Tell us about your initiation into music and training.

Ust. SK: I was initiated into the world of music at the age of 7 by my grandfather Ustad Haji Mohammad Khan. Apart from him, I learnt from my other grandfather Ustad Allan Khan, my father Ustad Chhajju Khan and my uncle Ustad Laddan Khan.

My grandfather used to wake me up early morning and take me to the mosque to offer prayers. We used to come back and then he taught me for a few hours before I got something to eat. Then I was sent out to the bazaar to procure household items. After the afternoon prayers, I used to sit and do riyaaz with my grandfather for 3-4 hours. In the evening, I was given free time to play and then my training resumed in the night unto around 11. On the whole, I used to learn and do riyaaz for about 7-8 hours everyday.

My uncle Ustad Laddan Khan was a great sarangiya and lived with us in the last days of his life. His style of sarangi playing was very difficult to follow. There are some taans which one can only listen to and feel amused over but it is impossible to learn them without proper guidance. He gave me a wealth of such rare musical knowledge. My father used to travel around a lot. On an average, he used to be away from home for about 6 months every year. Sometimes, he took me along and gave me lessons while he was touring and visiting his other disciples.

IZ: Tell us about your journey in music and your career.

Ust. SK: At the age of 12, I went to the All India Radio (AIR) for the first time to give an audition. They failed me. I went again at the age of 14 but I was failed again! My grandfather asked me what kind of questions they asked and what they asked me to play and then told me that the queries were unfair to be asked of a 14 year old boy. However, these failures strengthened my will to practice more and polish my sarangi playing.

I went to the AIR once again in 1942 (at the age of 16) and was taken by the Tamil orchestra unit on a monthly renewable contract at Rs. 50/- per month. In 1943 I became a permanent employee and my pay was raised to Rs. 75/- per month. I was elated to become a permanent employee but the problem was that I did not know any notation and was thus always seated far away from the microphone and asked to be quiet. The person in-charge of the orchestra, Mr. S. Krishnaswamy, asked me one day which language I knew to read or write. I only knew Urdu so Krishnaswamy took great pains to learn how to read and write in Urdu and then figured out a way to write notation in the same language in order to teach me. This gave me a lot of strength and the will to learn the Tamil language in reciprocation, which I did. After a few months, I was able to read Tamil notation and sit with the others in the orchestra confidently!

In 1946, I was taken by the Delhi orchestra unit. Two greats used to compose orchestra in this section at that time – Ustad Chand Khan and Pt. Laxman Prasad Jaipurwale. Subsequently, I also played in the orchestra of Sh. Jeewanlal Mattoo, Pt. Pannalal Ghosh and Pt. Ravi Shankar.

IZ: It seems as if you played in the orchestra a lot! How did you manage to become a sarangi soloist and such a fine accompanying artist in classical music?

Ust. SK: (With a twinkle in his eyes) This is a very interesting story! With time and experience, I became a very good member of the orchestra, be it in the Tamil unit or in the Delhi unit. None of the composers wanted to let go of me but I always wanted to become a good soloist and a skillful accompanying artist in the classical section. Then, I made a crucial and mischievous decision. I decided that I would now start ‘forgetting’! That seemed to me the only solution at that time for getting transferred to another section or otherwise I would remain stuck in the orchestra for the rest of my life!

When I started ‘forgetting’ in the orchestra, I was promptly transferred into the light music section. I came under Sh. Roshanlal Nagrath (grandfather of the popular actor Hrithik Roshan) who used to compose preludes and interludes in the light music section. Very few people know this but he was a very fine jaltarang and dilruba player as well! In the light music section as well, after a while, I reverted to my trick of ‘forgetting’ since my aim was to get into the classical music section!

In the classical music section, I was faced with another problem. No good artist wanted to take me as an accompanist! It was only with time and with Allah’s blessings that I started getting a few programmes and then the rest, as they say, is history. I accompanied greats like Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Ustad Amir Khan, Ustad Khadim Hussain Khan, Pt. Krishnarao Shankar Pandit, Pt. Omkarnath Thakur, Mallika-e-Mausiqui Roshan Ara Begum, Smt. Rasoolan Bai and Pt. Bhimsen Joshi among others.

Sabri Khan and Bhimsen Joshi

All said and done, I had a wonderful career in the AIR and worked as a permanent employee from 1943 all the way unto 1989!

IZ: Do you feel a sense of fulfillment at this stage of your life now?

Ust. SK: By the grace of Allah, I have traveled far and wide and visited many foreign countries such as USA, UK, Germany, France, Japan, China, Afghanistan and Pakistan. I have also had the opportunity to play at every major festival and in every prominent city within India. At the age of 78, I continue to impart training to my students and feel very happy seeing their growth as successful performers in their own right!